This article was first published in the First Round Review.

It’s 3 a.m. and my phone vibrates. “This can’t be good,” I think, rolling over to read the one text message I never wanted to see: the AppDirect platform is down. No one has been able to use our partners’ applications for hours. And if we don’t fix it now, tens of thousands more will be locked out by morning.

Frantic, I start making calls to engineering leads. “Someone has to know what’s going on,” I think. “But who?” Finally, I’m able to round up an ad hoc team to get the site back up, but not before wasting precious time, waking a dozen colleagues, and spiking the team’s blood pressure.

A year later, we had protocols in place for these types of challenges. But it didn’t happen overnight. We had to learn on our feet as we grew over 500% in that time. Ultimately, several very practical lessons emerged. My goal is to save you the time and trouble of learning them the hard way.

When you’re growing beyond 10 or 20 people, there’s a truth you’re probably reluctant to accept: You need organizational structure. New faces keep showing up wondering where they fit in. And people need to be empowered to lead. At AppDirect, we had to reinvent our approach to this several times before it worked.

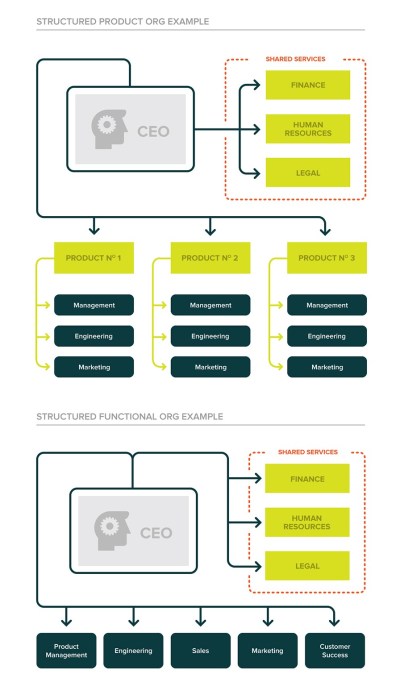

We started building our teams with a simple functional structure: product managers working as a product team, account managers working as an account team, and so forth for engineering, sales, marketing, customer support, QA, and partnerships.

But we hit a wall quickly — the new functions created gaps in how teams were collaborating between groups. It is hard to close deals if you can’t pull in expertise from marketing, engineering, or anywhere else you might need in the company. We eventually moved to a more diverse team structure around big accounts. But to make this possible, we had to put stakes in the ground.

How to Build an Org Chart

To say we were nervous about rolling out our first org chart is an understatement. People who work at early-stage startups are not easily confined to boxes and lines. Most of them are generalists, and here we were trying to split them up into more specialized roles, narrowing the scope for some of the earliest employees as we brought on more people. We were also anointing managers where there were none before. We didn’t expect easy buy-in.

What we discovered surprises some people: the team actually embraced having more org structure. Defined roles freed people to do better work, take clear ownership of projects and drive results. As we grew, we rolled out second and third versions of the org chart, and each time we received a positive response. Looking back, there are several reasons this worked so smoothly:

- Most people actually like structure. It’s human nature to a certain extent, but even entrepreneurial employees appreciate guide rails to direct their focus. More on this later.

- We rallied our stakeholders. We discussed the changes in advance with key and influential team members so they understood our rationale and became internal advocates.

- We communicated improvements. Every time we changed team structure, we made it clear how they were improvements from the status quo. We reinforced changes until they became ingrained as part of our culture.

At a startup, boxes-and-lines organization can run against the grain. Entrepreneurship is typically defined by its flexibility — an “everyone pitches in” energy that makes initial momentum possible. But this breaks down when you add more people.

By introducing structure early — even earlier than you might want to — you set the scaffolding for excellent teams: small groups of talented people working together on shared problems. Org design becomes core to your success. And if you do it right, teams are able to accomplish more than the sum of their parts.

If creating effective teams is half of the problem, learning to delegate is the other half.

“ORGANIZATION CAN RUB FOUNDERS THE WRONG WAY, BUT ONLY THOSE WHO CAN PASS OFF AUTHORITY SURVIVE.”

It starts with trusting your employees, and that starts with hiring. You should only hire people you would trust to make decisions without you. That’s the bar. Especially for leaders.

When are ready to create structure, ideally when you have 20-something employees, there are a few tactical steps you can take to implement a strong organizational structure:

1) Decide what kind of company you are. Start by actually writing down what you will need for your company to win. What is truly important? Do you need to nail product design? Do you need to allocate more resources to sales? Do you need to internationalize to stay competitive?

Most companies need to excel in several areas to succeed. For example, enterprise software startups must deliver not only world-class sales, but also tailored product integrations that meet customer expectations. But some competencies will matter more than others. You can’t be good at everything, so know what you absolutely have to be good at.

2) Create groups that make sense. Start breaking out teams with the above in mind. Certain roles should be empowered within teams to align with the type of company you want to be. For example, if you’re a product-first company, PMs should occupy leadership roles unifying teams. If marketing drives most of your business, marketers should be placed in key decision-making positions.

Remember to make choices with future employees in mind. Where will they fit in? To drive this home, actually sketch out an org chart — or even several variations — filling in existing employees and leaving blanks to inform your hiring plans. Of course, you will need to revisit and refine your org chart after initial rollout, but this will keep you thinking ahead.

As you draft these charts, roles will inevitably become more specialized. For instance, as we added account managers at AppDirect, we created two groups: people who were good at relationship building, and people who were good at product implementation. Similarly, as our sales team grew, we decided to bring on sales engineers, freeing up other engineers to focus on improving the product.

3) Get input from key players. For any org chart to take root, you need it to be embraced by the most important people at your company. You know who they are — at minimum they include your cofounders, active board members, trusted outside advisors, and senior executives (if you have any). Depending on the size of your company, this could include the head of HR. Focus these conversations on refining what you’ve already sketched out, rather than going back to the drawing board each time.

4) Clearly (and loudly) communicate your plan. This is probably the most important yet most delicate step. Organizational changes require employees to buy-in for it to be successful. And for many employees — especially those most affected — org changes are very sensitive. Not only do they impact everyone’s day-to-day activities, but often their perceptions of themselves as valuable members of the team.

“SURPRISING PEOPLE CREATES FRICTION AND HOSTILITY.”

People may be reporting to someone other than the founders for the first time — this could feel like a demotion, or like their contributions didn’t matter. Others may see their responsibilities significantly narrowed. For these people in particular, you need to invest one-on-one time before a broader announcement to explain your reasoning and have an open dialogue. Otherwise you’ll end up with unnecessary friction.

5) Implement quickly but thoughtfully. You want people to start seeing the changes you announced right away. At the same time, you want to pay special attention to new team leads. These roles are the lynchpin in your plan. Make sure they are on track to build and support teams that work. Spend the time and resources to get them the training they need to manage people well.

6) Don’t be afraid to tweak. Your first schematic will not be perfect. As your company grows, as leadership learns, and as your strategy and markets evolve, you will want the ability to break your own system and make changes. Pay attention to what’s working and what isn’t.

Ultimately, a good org chart tends to follow a few principles:

- It links: You can create strong links in two ways. The first is to create processes and culture around how groups work together (more on this below). The second is to unify leadership over groups that need tight coordination. For example, where groups are only connected at the CEO level, it’s the CEO’s job to make sure they are working well together.

- It reaches: As much as we’d like to design ideal organizations, it’s better to focus on designing an organization that fits the people you have now and the resources you have to grow only in the near-term. The best org chart strikes a balance between what you want in the future and the talent and resources you have today.

- It flattens: Identify the specific value created by each level of hierarchy. If you can’t, strike it. I use a loose rule of thumb that an experienced business manager can directly manage a team of about a half-dozen, and an engineering manager can handle double that. Executives should try to avoid more than a half-dozen key reports — which is why who you hire for your top-team is so critical.

- It simplifies: Employees don’t thrive in complex org structures, and if your org chart has too many lines, matrices, and overlaps, ask yourself if you can slim it down to the most essential core teams and roles.

- It predicts: It’s well known that some people who are good leaders early in a company’s growth might not be up to the challenges of scaling. As you build your org chart, it should force you to think about who is growing at the right pace to take on the challenges of a larger company.

Layer in Process

Not too long after I started at AppDirect, I came in to find one of our senior executives panicked over an email from one of our most important partners. “This is no way to work together,” the email began. The partner was angry. And with good reason. We had just pushed a major interface change without first notifying the partner, derailing a major promotion they had in the works. It was painfully obvious: We hadn’t (back then) built a good process for communicating major changes to partners.

Rapid growth requires serious focus on process. As soon as you start adding new people, roles, departments, you add more handoffs, more breakdowns, and more ambiguity about who does what, when, where, and how. The hard part is introducing process without the heavy bureaucracy that slows startups down.

At AppDirect, our most complex process is the way we design, scope and deliver new products. Early on, bringing on a large new customer would often take weeks or even months from initial discussions to completion. And it would take dozens of people across functional areas (plus lawyers) to move a product along. Too often people didn’t know what their involvement should be, leading to bottlenecks and breakdowns, wasted time, inconsistent standards, and a lot of frustration.

We knew there had to be a better way. But we also knew that our product integration would always require a lot of people. There was no way out of that. So here’s what we did:

1. We consolidated ownership and accountability in as few people as possible.

2. We identified what routines, needs, and actions were frequent — and we standardized them. This allowed us to break big efforts into more digestible steps and assign them out.

3. We positioned account managers and technical project managers as the two end-to-end owners of deals. They became accountable for overseeing everyone else involved, in essence reducing dozens of handoffs down to one. This dramatically reduced miscommunications and dropped balls. Generally speaking, you want as few owners as possible.

4. We vigilantly documented every step required to complete the work. Then we went back and killed innumerable steps until we arrived at the simplest flow possible.

The goal is always to anticipate and implement process before there’s a problem. As you grow, several of the highest-priority processes include:

- Product sprints, code reviews and QA

- A/B testing, product change requests, product roadmap planning

- Financial planning, budgeting, expense approvals

- Hiring, performance reviews, bonuses, equity grants, promotions

- Customer support flows and escalations

- Sales contracting and pricing

Most processes are little more than listing out the steps someone needs to take to get the work done. Few people take the time to write down the who, what and when.

“THERE ARE MANY WAYS TO GET FANCY ABOUT PROCESS. DON’T.”

Focus first on creating lists of repeatable steps to get common workflows done — and make them as short as you can. At AppDirect, our quarterly product roadmap process was essentially three steps and a calendar of deadlines. Even our most complex process — scoping and negotiating contracts for novel product integrations — ended up being only 20 steps. It started out much longer, but after dozens of tweaks we got it streamlined.

Most importantly, rely on the employees closest to the work to help you craft these lists. They have the most insight into the day-to-day challenges and ways to do things better. Listening to them will also create a feedback loop that allows you to continually adjust and improve. One hallmark of good communication is that employees will come tell you when things are broken.

Use Metrics to Your Advantage

At AppDirect, I worked closely with our customer support team to build a custom monthly dashboard of metrics. We felt that off-the-shelf reports from our customer support software didn’t really reflect what we needed to know. Building custom metrics was worth the effort: I remember how the insights jumped off the page of the first dashboard — there were whole clusters of technical tickets routed to engineers that could have been handled much earlier by our support and QA teams. With this data in hand, we were able to overhaul how tickets were routed the very next day, freeing up hours of engineering time.

“NUMBERS ARE ONLY AS VALUABLE AS THEIR ABILITY TO DRIVE DECISIONS AND CHANGE.”

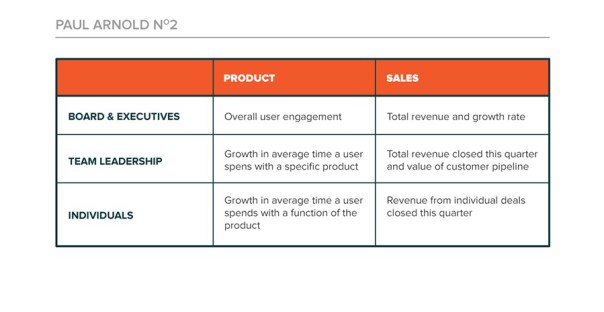

The bigger you get, the more vital it is for leaders to have tools that give them quick snapshots of what everyone is doing and where decisions need to be made. To build these tools, you must 1) decide on the metrics that are most critical to executing your business (and not too many), and 2) put systems in place to collect and track these numbers efficiently.

A few key considerations for designing better metrics:

- Make sure they are relatively easy to collect.

- Only use metrics that are tied directly to your goals and values.

- Most importantly, keep your metrics actionable.

To get the most out of your metrics, cascade them from the top down. Start with your top company goals (for example, user engagement or revenue). Then ensure that your functions and teams have metrics that directly drive toward these goals. After that, look at the individuals who make up these teams. They should each have personal metrics, also aligned with their team and the organization. With this approach, you make sure everyone is motivated and aligned toward true north.

Experiment and Drive Change

Across all these areas, there is a common thread for success: Always be experimenting. Create new roles, processes, dashboards, and communication channels. Be creative. But remember to go back and ruthlessly prune. Rethink how things can work better, faster, simpler.

No matter how hard you try to get things right the first or the fifth time around — you won’t. Focus instead on generating new ideas, killing the bad ones and starting over. Growth requires constant reinvention. And if you can bring everyone along for the ride, you will succeed.