Think about some venture funds. Now think about their approach. What comes to mind? Do they focus on a particular geography or technology trend? Or invest alongside their most famous friends? Maybe their partners have built large personal brands. Or they have an operational platform to support their companies' growth.

My view is that there are only three truly distinct venture fund strategies, and all of them boil down to one point: Can you change the distribution of the companies in which you invest? Among the many approaches in venture capital, there are fundamentally only three ways to do this. The best funds pursue all of them.

Add Value

Source Better

Invest Better

That's it. Everything else is tactics and execution. Any strategy that doesn't achieve one of these is puffery, marketing, or confusion.

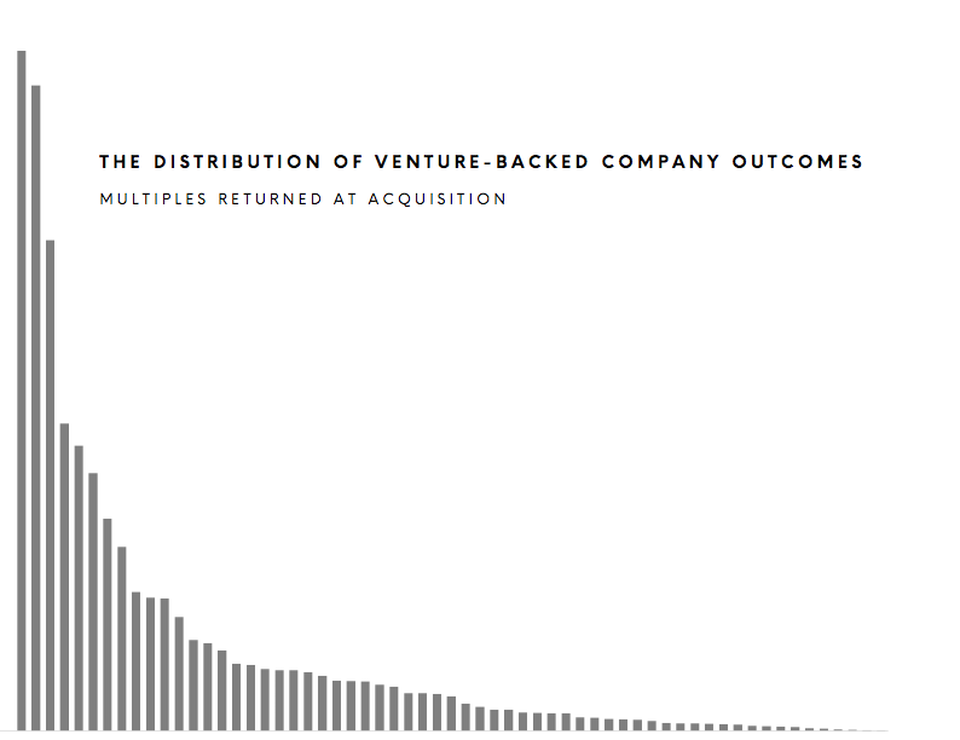

The power law of returns dominates startup investing. Much has been said on the topic (like here, here, here, here, here, here, or here). What matters for a venture strategy is that nothing is more determinative of a fund's success. Power-law distribution is the architecture of the whole game.

I measure any investing approach against its impact on the power-law distribution. This is the acid test of what is actually effective. And while it is true that adding value, sourcing better, and investing better are all good strategies other investing situations, the effects, especially of 2 and 3, are especially significant in venture where the power curve has a large exponent.

Most VCs invest somewhat randomly along the power curve of opportunities they see. Over short periods of time, this randomness can result in good or bad funds. Over longer periods, mediocrity will set in as their investments regress to the mean. They will have weak persistence of performance.

Switch has thankfully done well, with top 5-10% venture fund performance. I feel lucky. And I know that there is a lot of hard work ahead. Beyond a good measure of luck, I credit thinking hard and often about this fundamental power-law game.

Above is a distribution of investment multiples returned on acquired companies. The graph shows 50 acquisitions that an investor could have invested in, with five hypothetical investments in orange. This is a subset of a related power-law—the outcomes of all companies a given investor sees—but with the tail of failed companies removed.

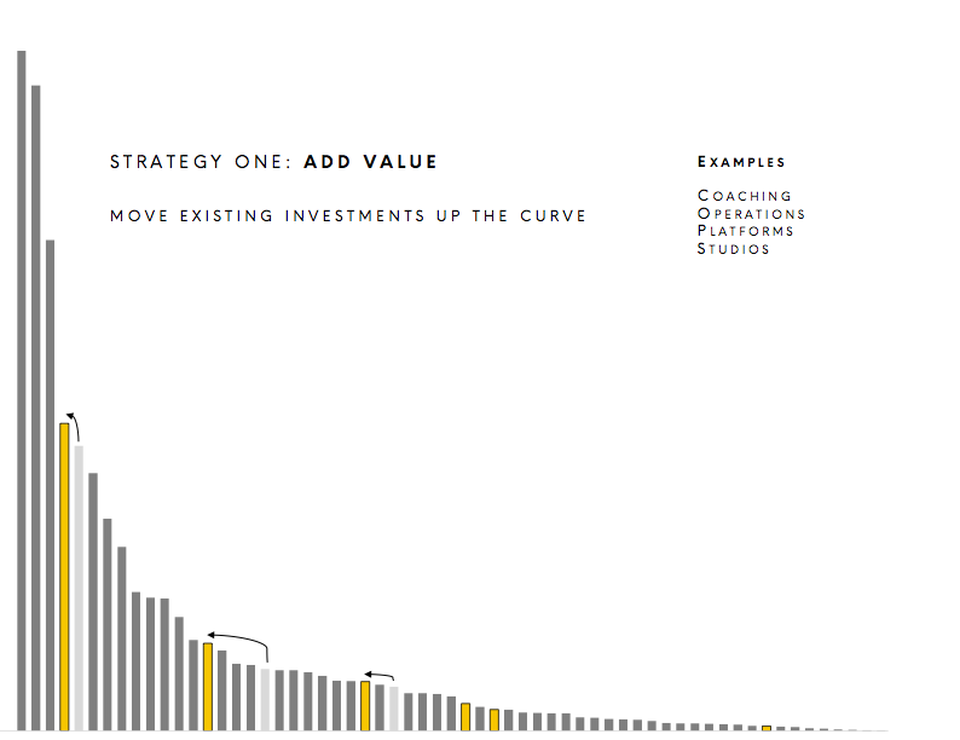

1/ Add Value

Adding value is a real strategy because it moves existing investments up the curve. It increases the return on an investment. Investments move up the tail of the curve because of the value the venture investor creates.

Improving portfolio company operations is the most common approach. Recruitment, marketing, partnerships, sale, operations, and board support are common areas to help. Most often this takes the form of coaching founders or rolling-up your sleeves to help them get work done. Some funds institutionalize value-add through software or platform teams. Startup studios are interesting, blurring the lines between founders and investors.

My view is that adding value is absolutely necessary—it's the promise to your founders to be their partner. And it earns you the right to be involved with great founders. Ultimately, great founders in great markets build great companies. You won't make it in venture if you don't work with them. And you won't work with them if you don't bring value to the table.

For founders, an investor's ability to add value is obviously important. Great founders are choosing their investors and want to bring in people who will help build the company.

Of the three strategies, adding value is the least unique in impact here. In a much flatter distribution, as you see in say leveraged-buyout private equity, adding value will create about the same level of value that it will in the power-law distribution. The next two strategies, however, have markedly higher impacts in the power-curve setting.

2/ Source Better

Sourcing better is a real strategy because it rescales the distribution. Even a random selection of investments from a better-sourced distribution of companies will have a higher expected return than an average venture fund. Fishing in a better pond can make as much (or more) difference as being a better fisherman.

A classic way to source better is to build a better network. This works for firms with a strong general reputation. It can also work if you are deep in a particular group of exceptional people—say, globally-elite AI researchers. Focusing on a geography can create strong networks if a fund establishes regional dominance.

Quantitative venture investing can have a huge impact on picking the right investments. Admittedly, I'm biased. A predictive-analytic approach to teams, companies, and industries stacks your hand from the start. It changes all the investment odds. This takes much work to do well but has attractive returns for the effort.

Outbound sourcing is an under-appreciated approach in early-stage venture. Because inbound referrals are plentiful, investors often ignore outbound efforts. The key is being able to target founders who actually are exceptional. But if you can, why would you not make sure you are talking with the best out there?

Switch aspires to take several of these approaches: using a mathematical and predictive approach to sourcing, building high-quality and selective networks of founders that spin-out many great companies, and proactively reaching out to the founders who excite us most.

Founders want investors who already work with great startups, because the investor can help more, has relevant experiences scaling successes, sends a signal that they too run an exciting startup, and so on. Everybody is better off for the company they keep.

3/ Invest Better

Investing better is a real strategy because you end up in bigger winners. It increases the frequency in the upper tail of outcomes. In the graph above, investing better switches the five investments from light-grey to the new orange bars.

Picking better is the dominant way to achieve outsized results at the seed stage. And the most important factor for picking better is, by far, good judgment. Good judgment is hard to describe. It's a somewhat ephemeral quality, which only reveals itself over time. As Bill Gurley says, it's the single most important quality he looks for in a new investing partner.

Picking better is also a function of doing research and developing insights. Having a correct industry thesis is a perfect example. If you can predict major technology and economic trends, you will be rewarded with more hits.

An approach taken by growth-stage firms like Battery and Summit is less about picking to drive alpha, but to reduce beta. The thinking is to choose and structuring safer bets. These firms certainly still play on a power curve, but they are able to invest on a less dramatic one, lowering the exponent of the curve. I do not, though, see this as a strong approach to investing at the early-stage.

Art and science (or guts and brains) both play into picking. And both are hard. In most firms, there is a huge variance of performance between partners.

Access becomes a much more important factor in the later stages of venture. This is because the winners start to become very obvious as time goes on. Most Series C investors have very similar lists of the top ten companies they would like to invest in. Brand and reputation have increasing payoff as you move into later-stages.

I strive to always sharpen my judgment. I try to test and improve my decision-making. For me, this involves a lot of reading, a lot of critical reflection, and perhaps most importantly, testing my ideas critically with other investors I respect.

Founders want to work with VCs who invest better for the same reasons they want to work with VCs who source better—they want people to associate them with the best. It sends a positive signal to customers, employees, and other investors. And it's a more valuable network to be a part of.

Putting It to Work

These three strategies will not look the same or be equally relevant for all funds. There are many ways to execute, and the winning approach depends on the investment stage and people involved. And while all three strategies add portfolio value, resources are limited and a fund should think through which can add the most for them. Finally, there is some logical order to developing capabilities. For example, if you can't source at least some great deals, you really won't be able to pick great ones either.

Grounding venture strategy in power-law thinking has consistently been helpful for me, and hopefully can help others add a frame to their approaches too.

I also published this post in Forbes.

Thanks to Ian, Jonathan, Dan, Alison, Samir, Marc, and James for sharing your thoughts on this post.